The Hastings fishing fleet is one of the oldest in Britain. As EU restrictions and intensive fishing methods threaten this traditional way of life, Alastair Hendy takes to the sea to find out more.

‘The tide is high, cold water rakes shingle, and the fisherman call to each other in the dark. An unknown dawn, an unknown catch, dithers far out in an unfriendly sea.’

The sweep of The Stade from Rock-a-Nore groyne to the collapsed harbour wall; the line of clinker built boats; the piles of net and cuttle-pots; the fisherman’s huts and the whiff of fish, diesel and pitch. Little has changed over the past fifty years on Hastings beach. The fishing fleet has diminished in size, granted. UKIP flags flutter. And there are plenty No To Jerwoods: graffitied protests still in place to an ill-placed art gallery that went up years ago – its only catch-of-the-day being some Chapman Brothers butchered human bits. But at 2.30am all is seriously dark and most unfamiliar.

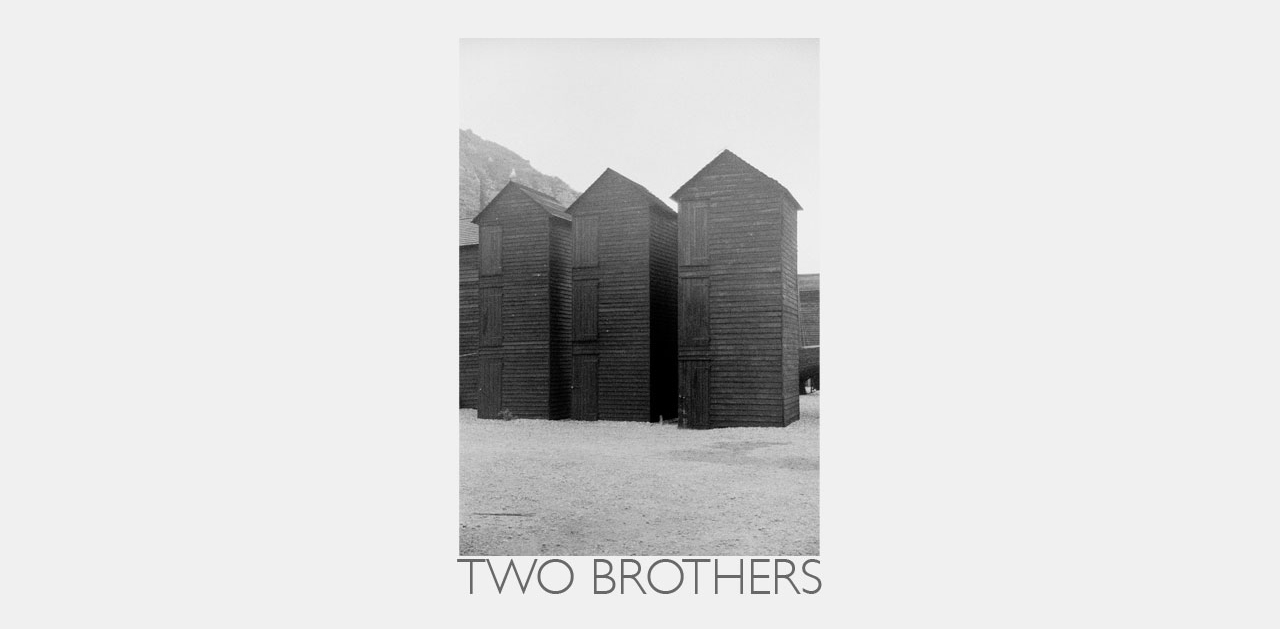

The tall sheds stand in closed ranks, watching, whispering – as inky black as the cliffs behind them. Their Jerwood grumblings clotted with tar. And the brightly painted boats are now unfriendly bitten shapes in Chapman greys. Somber exhibits. Leviathons from The Deep, stranded in a no-mans land of highly seasoned fish flavoured darkness. The tide is high, cold water rakes shingle, and the fisherman call to each other in the dark. An unknown dawn, an unknown catch, dithers far out in an unfriendly sea.

At a winch shed labeled Two Brothers, fishermen Paul Read, owner of boat RX59 and Pat Joy, his helper, don oil skins, rubber and gloves. Distant boat sounds of hard work steal moments in the silence. A bulldozer, weary with rust, chokes on its salt, and stammers into action and RX59 is nudged down the stones and delivered to the water. Until quite recently this was a hands-on job – men pushed on the prow with shoulders and rolled-up shirt sleeves. The mechanical shove came to the rescue only some thirty years back.

This beach is still a Working Beach. It is more builders yard and slaughter house than pretty dock. Leisure and sun-bathing have no place. Yet relaxing with a packet of fish and chips does, mid the effluvial litter of desiccated dogfish leather, crab carapace and unhappy dead limbs from the deep. Tracts of The Stade (Saxon for Landing Place) are owned by families that have been in the sea-faring business for centuries; a fringe community who still battle to graft a hard-earned crust from local waters. Their trade is in flat fish – plaice, Dover and lemon sole, flounder, dab, brill, halibut and, when luck has it, turbot. Delicate plates of meat. The glassy-eyed voracious feeders, cod and whiting are landed in winter. Cuttlefish, whelks, crab, grey mullet, skate, mackerel and sea bass are potted and hooked throughout summer. It’s no wonder then that fish and chips or a tub of boiled whelks are the unofficial ticket to enjoying a stint on the pebbles. Fish and chips is the only local help on offer in the propping up of this floundering industry. Most of the catch gets whisked off to Spain.

The fleet is one of the oldest in Britain; a few of the boats still soldiering-on from the 1950s. By then diesel engines had replaced sails and paraffin motors; boats were no longer pulled up the beach by horse and capstan, but by steel cable and motor; and the end of the decade saw nylon nets. Fishing methods, however, haven’t changed much since the 18th century. The beach launching of boats is labour intensive, restricting the numbers that can operate. This procreates a natural and environmentally sound conservation process, which, according to the government’s Sea Fish Industry Authority, is “as near perfect a fishery as could be devised”. And this is seconded by the pat-on-the-back endorsement of the Marine Stewardship Council.

However, the Hastings fisherman could soon become extinct. Paul Joy, chairman of Hastings Fishermen’s Protection Society, reiterates yearly that the fleet is currently struggling because of the quota distribution system set by the European Union (EU). This is policed by Defra’s Marine and Fisheries Agency who appear to be over zealous with their monitoring of a fleet that can barely afford to set sail. At present more than 90% of the allocation goes to large fishing firms armed with heavy-duty beam trawlers. This leaves small marine-friendly fleets, like the one in Hastings, the scraps of the quota. Fisherman together with local politicians continue to fight for a fairer system – to avoid the insane dumping of fish fit-for-the-pot, back into the sea. Every year is the same story, the chapters of which are barely punctuated with moments of joy.

We launch on a fast ebbing tide and chug out through a thick mist full of doubt. Pat makes mugs of tea with a dash of UHT. Then the sun peeps out, if but with brief hope. The dawn fog slips back into the water, and the competition is unveiled. Far out toward The Channel sit two commercial beam trawlers contentedly hoovering-up the seabed. “Since Britain joined the EU these beamers have remained a pain, frequently straying off limits in to the six mile Hastings fishermen’s zone” says Paul. The 1983 Common Fisheries Policy agreement that sited these zones would appear to need further enforcement.

The sea begins to heave. Vast, murky, indigestible, shifting slabs of it. The first of the buoys slides into view, marking the beginning of two miles of trammel net: a triple layered curtain descending to the sea floor. The swell sends horizons sea-sawing. You feel it. Legs, knees and throat. The net and the Entangled pour in through mechanised rollers. Fish today is scant, spider crabs full-on – as is ‘gully water’, the brown noxious slime of spawning plankton. The barnacled spiders unwieldy limbs and thorny excrescences clog the nets like gooseweed on socks, so an angry hammering to beyond oblivion is their fate. We finish up with two crates of fish and crustacea carnage: a heaving deck awash with crab brains and putrescence, and a few despairing hermit crabs, noses put-out, searching for an exit. Paul and Pat in their splattered rubbers, now wear unsolicited gully water face-packs. Give me Land.

9am. And the boat makes happy going-home noises. Seagulls follow us in a pecking-each-other yelling frenzy all the way back. The small catch – seventy sole and the same of plaice – go to the fish market to be auctioned, destination Holland, France and Spain. Our discerning neighbours recognise our delicious sea assets. We appear to prefer ours in Sea World. And, more worryingly, only acknowledge our fishing fleet when repackaged through the windows of an art gallery. Bloodied heads and spinal chord tossed to the gulls by the fishermen working below the Jerwood’s balcony is now theatre. For some, it is Art.

A well-aimed stone’s throw away, and up the stairs of Maggie’s fish and chip shop, mugs of tea and practical formica restore faith and stomach. Stuck up on the wall is a fine piece of art: a fibre glass model of the largest plaice ever caught. It had broken all records, weighing in at 20lbs, and had been caught in Hastings waters. “Caught a couple same as that last week” Pat said, “about half the size”. We drank our tea.

How to cook and eat flatfish

My grandparents lived on the outskirts of Hastings. They’d buy plaice and chips from The Dolphin Bar, park up on the front and eat it on plates with cutlery kept in their Austin 1100’s glove compartment: a set for two with salt cellar, cushioned by the driver’s well-thumbed Austin handbook, and permanently kept there for such marvelous occasions. When buying fish wet, they’d get it off the boats, from the boy ashore at the back of the winch sheds. Fresh fish straight from the sea, bought from a scrubbed plank, is an honest and winning option.

Flat fish need the simplest of cooking. I remember the plaice still alive, flexing and cavorting in its newspaper on the kitchen draining board – the skin shimmering, dappled with rust-coloured spots, and stuck with wet paper. A thick clump of parsley for sauce and runner beans in the sink – both picked straight from the garden. With peeled new potatoes on the boil, the fish was floured and briefly fried. Bone handled fish knifes and forks were lifted from their black velvet lined box, and the table laid with the best cloth and plates. This simple meal was always perfect – and for me, it is the only way to eat flatfish.

To grill

Preheat the grill until raging hot, as this will crisp the skin. If your fish is extra large, make diagonal slashes in the thickest part. Brush with oil or melted butter, sprinkle with salt and pepper, adding woody herbs if you have them, and cook until just done. Part the flesh with a tip of a knife, to check the flesh is not still transparent near the bone. About 5 minutes for a medium sized fish, and 8 minutes for something more family-sized.

To poach

Put water, 1 sliced onion, 2 sticks broken celery, 1 sliced carrot, a bundle of herbs and some lemon slices into a wide shallow pan – big enough to fit your fish. Season well and bring to a boil, then gently simmer for about 20 minutes. Next slip in the fish, the liquid should just cover. Bring back to very gently simmer – barely a shiver – and poach for between 5 – 10 minutes, until just cooked through.

To fry

Season your fish and very lightly dust with flour. Add a good knob of butter and a drop of oil to a frying pan and heat until foaming. Slip him in, upside down, and fry for about 3 minutes, then carefully and deftly turn over and fry for 2 minutes more. A large fellow may need a few minutes more.