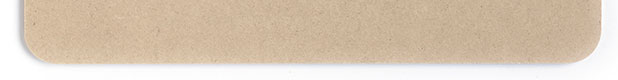

Battersea Power Station

Like something out of Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis, Battersea Power Station, London’s iconic landmark, has risen from its ashes in full futuristic splendour. This magnificent cathedral to the machine age has at last shaken off its post-apocalyptic past of abandonment and neglect, and has been completely rebuilt and meticulously restored, and is once again a towering monument to a brave new world. Yet its reincarnation and purpose has been completely reimagined – to the world we now live in: of shopping, dining and high rise living. So when next in town, go visit!

Designed in the 1930s in brick cathedral style – what we now call Art Deco – the power station’s turbine halls now house shops, restaurants, cafes and luxury apartments. A great behemoth, a beast of a project, that was failed by so many, has finally come to fruition. With 1.5 billion pounds spent, which included an underground train line extension, the Grade II* listed Power Station now stands at the heart of a 42-acre development. The transformation and refurbishment started in 2013 and was steered by the architectural practice, Wilkinson Eyre, with the designs consistent with Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s original vision. And it is truly magnificent.

It’s been a long road, so it’s important to grasp some basic history and the sheer scale of what has been involved. The original building comprises of two power stations, built in two stages, and housed in a single building. Turbine hall A was built 1929 – 1935, and hall B, to its east, was built 1937 – 1941. Work on B was halted during WWII, and the building was completed in 1955. “Battersea B” was built to a design nearly identical to that of “Battersea A”, creating the iconic four-chimney structure. Coal arrived by boat and was unloaded by cranes at 480 tonnes per hour, and delivered to the station by conveyor belt.

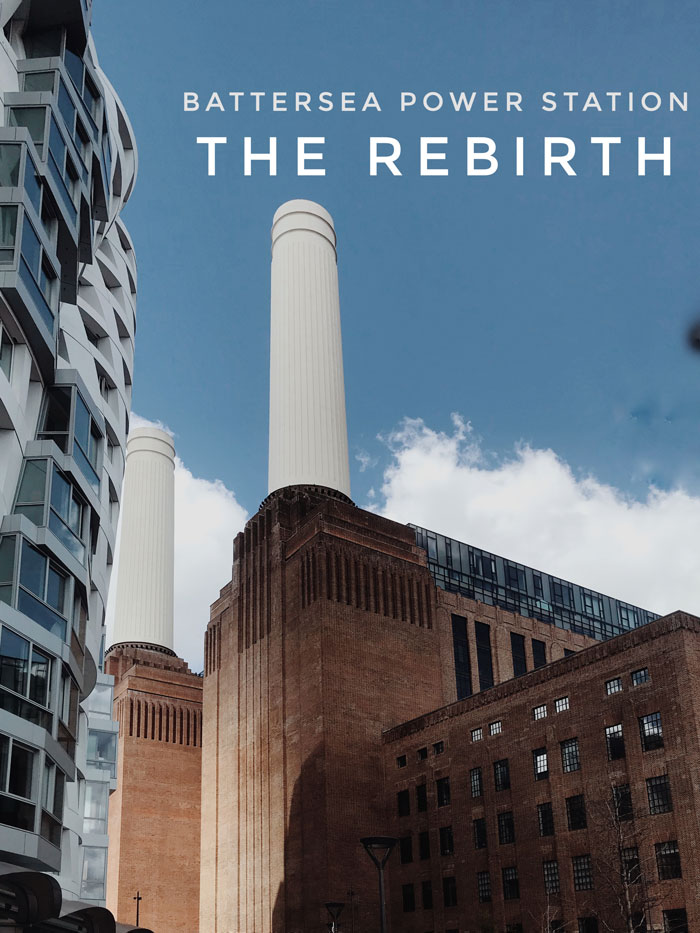

The Pig

Many of us might well have first fallen in love with Battersea Power Station when it appeared on the front cover of Pink Floyd’s 1977 album, Animals – complete with one giant pink floating pig. The inflatable pig was tethered to one of the southern chimneys but lost its moorings and rose into the flight path of Heathrow Airport. Police helicopters tracked its course until it finally landed off the coast of Kent.

Alton Towers

Following the station’s closure in 1983, the Central Electricity Generating Board had planned to demolish the power station and sell the land for housing, but because of the building’s new listed status, they had to pay the high cost of preserving it. In 1983 they held a competition for ideas on the redevelopment of the site, which was won by a consortium which included John Broome, owner of Alton Towers Ltd. An indoor theme park with shops and restaurants was proposed, yet at an estimated cost of £35 million, the scheme was risky and would require over 2 million visitors a year to make any profit. The scheme received planning approval and the site was purchased by Alton Towers for £1.5 million in 1987. Work began the same year.

The project was halted in March 1989, for lack of funding, after costs had quickly escalated to £230 million. By this point huge sections of the building’s roof had been removed, so that machinery could be taken out. Without a roof, the building’s steel framework had been left exposed and its foundations were prone to flooding and the rot set in, literally.

The Turbine Halls

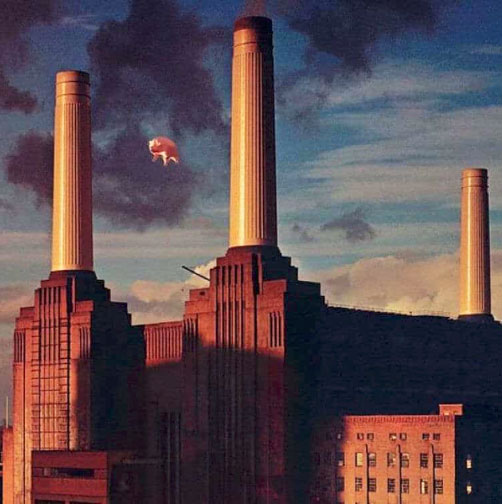

Turbine Hall A has been restored to its Art Deco splendour with the roof and end windows reglazed, having been covered up during World War II, they now allow daylight to stream into the space. The old gantry cranes and travelling rail have been left as raw reminders of the past, as are the knocks visible on the faience at the southern end of the Turbine Hall.

In contrast, the beautifully austere Turbine Hall B reflects 1950s modernism, the faience, although the same colour, is smooth with no adornment. Its control room that overlooks the cavernous hall has been opened as a cocktail bar, set in amongst the original dials and controls.

The Chimneys

Testing of the chimneys showed the concrete to have high chloride content and to be carbonated, which had resulted in severe corrosion of the steel reinforcement. The extensive conversations that followed, between industry experts, the developers, the local planning authority and Historic England, confirmed the course of action required: all chimneys to be dismantled and rebuilt to the precise specifications of the originals.

The original 1930s architects’ plans and specifications were used to ensure the reconstructed chimneys were identical to their predecessors. This included over 25,000 wheelbarrows of concrete to be poured by hand into shuttered layers in each chimney. By doing this, the chimneys now have the same lifespan as that of the rest of the restored Power Station. One chimney now houses a glass lift, and it pops out the top for panoramic views of the power station, The Thames and London.

The Bricks

Its years as an active power station and weathering had left some of its six million bricks badly damaged. Unbelievably, the original brickmakers were tracked down and then tasked with hand throwing 1.75 million more to match the originals.

The family-owned business (now known as Northcot Brick) is still based at the same Gloucestershire quarry as it was all those years ago with access to the same Lower Jurassic and Middle Lias clay that was used for the original bricks. Northcot Brick provided 1.3 million bricks, all of which have been blended and hand moulded, to be used to restore parts of the Power Station built in the 1930s and 1940s; and Blockleys, in Shropshire, provided 440,000 wire-cut bricks to be used on the parts of the 1950s Power Station B.